Back Torium Afrikaans ቶሪየም Amharic Torio AN थोरियम ANP ثوريوم Arabic طوريوم ARY ثوريوم ARZ Toriu AST Torium Azerbaijani Thorium BAN

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thorium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈθɔːriəm/ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Th) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thorium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 90 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | f-block groups (no number) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | f-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 6d2 7s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 10, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 2023 K (1750 °C, 3182 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 5061 K (4788 °C, 8650 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at 20° C) | 11.725 g/cm3 [3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 13.81 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporisation | 514 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.230 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapour pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −1,[4] +1, +2, +3, +4 (a weakly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionisation energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 179.8 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 206±6 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centred cubic (fcc) (cF4) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constant | a = 508.45 pm (at 20 °C)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 11.54×10−6/K (at 20 °C)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 54.0 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 157 nΩ⋅m (at 0 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | 132.0×10−6 cm3/mol (293 K)[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 79 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 31 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 54 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 2490 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.27 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 3.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 295–685 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 390–1500 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-29-1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Thor, the Norse god of thunder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Jöns Jakob Berzelius (1829) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of thorium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

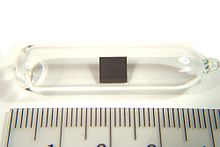

Thorium is a chemical element. It has the symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is a weakly radioactive light silver metal which tarnishes olive gray when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft and malleable and has a high melting point. Thorium is an electropositive actinide whose chemistry is dominated by the +4 oxidation state; it is quite reactive and can ignite in air when finely divided.

All known thorium isotopes are unstable. The most stable isotope, 232Th, has a half-life of 14.05 billion years, or about the age of the universe; it decays very slowly via alpha decay, starting a decay chain named the thorium series that ends at stable 208Pb. On Earth, thorium and uranium are the only elements with no stable or nearly-stable isotopes that still occur naturally in large quantities as primordial elements.[a] Thorium is estimated to be over three times as abundant as uranium in the Earth's crust, and is chiefly refined from monazite sands as a by-product of extracting rare-earth metals.

Thorium was discovered in 1828 by the Norwegian amateur mineralogist Morten Thrane Esmark and identified by the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius, who named it after Thor, the Norse god of thunder. Its first applications were developed in the late 19th century. Thorium's radioactivity was widely acknowledged during the first decades of the 20th century. In the second half of the century, thorium was replaced in many uses due to concerns about its radioactivity.

Thorium is still being used as an alloying element in TIG welding electrodes but is slowly being replaced in the field with different compositions. It was also material in high-end optics and scientific instrumentation, used in some broadcast vacuum tubes, and as the light source in gas mantles, but these uses have become marginal. It has been suggested as a replacement for uranium as nuclear fuel in nuclear reactors, and several thorium reactors have been built. Thorium is also used in strengthening magnesium, coating tungsten wire in electrical equipment, controlling the grain size of tungsten in electric lamps, high-temperature crucibles, and glasses including camera and scientific instrument lenses. Other uses for thorium include heat-resistant ceramics, aircraft engines, and in light bulbs. Ocean science has utilised 231Pa/230Th isotope ratios to understand the ancient ocean.[9]

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Thorium". CIAAW. 2013.

- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (4 May 2022). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b c Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ Th(-I) and U(-I) have been detected in the gas phase as octacarbonyl anions; see Chaoxian, Chi; Sudip, Pan; Jiaye, Jin; Luyan, Meng; Mingbiao, Luo; Lili, Zhao; Mingfei, Zhou; Gernot, Frenking (2019). "Octacarbonyl Ion Complexes of Actinides [An(CO)8]+/− (An=Th, U) and the Role of f Orbitals in Metal–Ligand Bonding". Chemistry (Weinheim an der Bergstrasse, Germany). 25 (50): 11772–11784. 25 (50): 11772–11784. doi:10.1002/chem.201902625. ISSN 0947-6539. PMC 6772027. PMID 31276242.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). CRC Press. pp. 4–135. ISBN 978-0-8493-0486-6.

- ^ Weast, R. (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. p. E110. ISBN 978-0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ Varga, Z.; Nicholl, A.; Mayer, K. (2014). "Determination of the 229Th half-life". Physical Review C. 89 (6): 064310. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.89.064310.

- ^ Negre, César et al. “Reversed flow of Atlantic deep water during the Last Glacial Maximum.” Nature, vol. 468,7320 (2010): 84-8. doi:10.1038/nature09508

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search